Do you want to understand terms like “genuine” and “top grain” and learn how leather is tanned? This is the guide you need!

Quality leather goods, whether shoes, luggage, jackets, or furniture, can be an investment in future enjoyment. The right leather paired with the right application can last a lifetime. The price tag often reflects this.

So, when you are in the market for a leather item, it’s important to understand what you’re looking at because purchasing the wrong leather, or an inferior leather good, is really just a waste of your money; and it is a huge market. The leather goods industry will reach $271 billion by the end of 2021.

Learning about leather grading really means learning about three separate areas: the animal the hide comes from and what area the hide the leather is from, the splitting of the hide or initial processing, and how the leather is tanned and dyed.

All leather starts as an animal hide. Not only does the quality of hides differ, but the type of processing or tanning makes a difference in how the leather can be used, and how durable the finished product will be.

There are many terms bandied about, and it’s important to understand them because they describe the processing from wet hide to finished item and will give you a clue about the quality of what you’re considering purchasing.

Leather Grades

Most of what will be discussed refers to cow hides – after all, this accounts for around 65% of all leathers available.

Other hides will be discussed later, but for now, think of bovines. Aside from availability, the leather from their hides is the most impervious to environmental factors once tanned.

The average cow hide will start out 6-10mm thick. Bulls will have a thicker hide because of their higher levels of testosterone. Most leather comes from steer hide (castrated males), and cows (females that have given birth).

These leathers are soft and work well for most needs. Heifers (females before calving) have hides that are softer and more pliable. Dairy cows have even thinner and softer hides, and finally, calfskin is the most supple and softest, with the tightest grain.

It has a lightweight feel similar to lambskin, although it is generally thicker.

You may have noticed that finer hides come from younger animals. The longer an animal is alive, the more there will be scars on the hide from scratches, insect bites, and wrinkles from fat.

In other words – just everyday living. I’m not saying that this makes a hide unacceptable, just that there are different uses for different hides.

The breed of cow, age, gender, and even weather conditions where it lived all affect the hide.

Within the same hide, the leather will have varying degrees of quality and usability.

- Grade 1: 15% of the hide. It has the most solid, closely fibered leather. It is also the thickest portion of the hide; there are few imperfections, and it resists water well. This is the portion of the hide that is generally sent to tanners for better leather goods.

- Grade 2: 30% of hide. This is still valuable hide although there may be up to 4 holes or cuts and grain defects that need to be worked around.

- Grade 3: 32% of the hide. This area has loose fiber and will sponge and swell in water. There may also be more holes/cuts and larger areas of grain imperfection. There should still be 50% of usable surface. The shoulder area is firm, yet malleable with a flexible feel.

- Grade 4: 25% of the hide. This area is softer and stretchier than other areas.

This is part of the grading system that has evolved for hides. 1st grade hides come from the top back portion of the cow. It is thick and smooth.

By the time you get to the legs and underbelly, the leather is thinner and has more markings and wrinkles. Leather from the underbelly has more stretch because it has expanded and contracted as the cow breathes and eats. For some purposes this is an advantage.

What part of the hide the leather comes from is just the first step in grading and finding quality leather goods, but it’s important to start with quality because no amount of processing can make garbage into luxury.

How the hide is processed really makes the difference between adequate and great. This is a 2-step process with lots of terminology to master: processing the hide into leather, and then tanning it.

Types of Leather

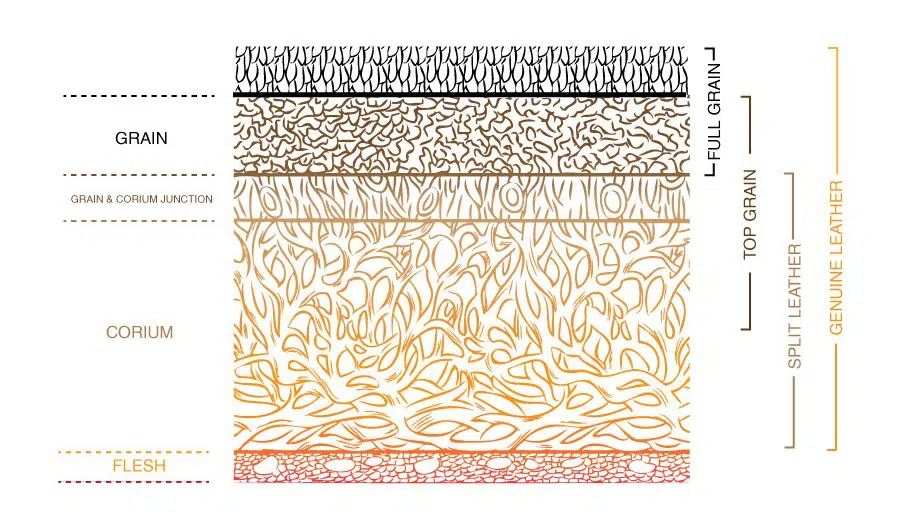

The outer part, where hair grows, is called the grain side, while the interior is the flesh side. The two parts are not equal in terms of usability.

Generally, all hides are split before they are tanned. The upper portion, seen in the diagram below as Full Grain and Top Grain, come from the outside layers of the hide. This is finer quality leather. Split Leather and Genuine Leather come from other portions of the hide.

You’ll notice that many of the categories overlap so the differences in labelling have to do with how much of each layer of Grain and Corium is included in the leather.

The more vertical the fibers within, the stronger the leather will be. That is why leather labelled Full Grain is the highest quality. It is made with only the grain of the hide, not the corium or corium junction.

Full Grain Leather

Full Grain leather starts out as the least processed – the hair of the animal has been scraped off, but the rest of the surface is untouched.

This also means that any skin imperfections from insect bites, cuts and scrapes, marbling, fat wrinkles, branding or stretch marks will show. These shouldn’t be considered defects but are instead a sign of the quality of the product.

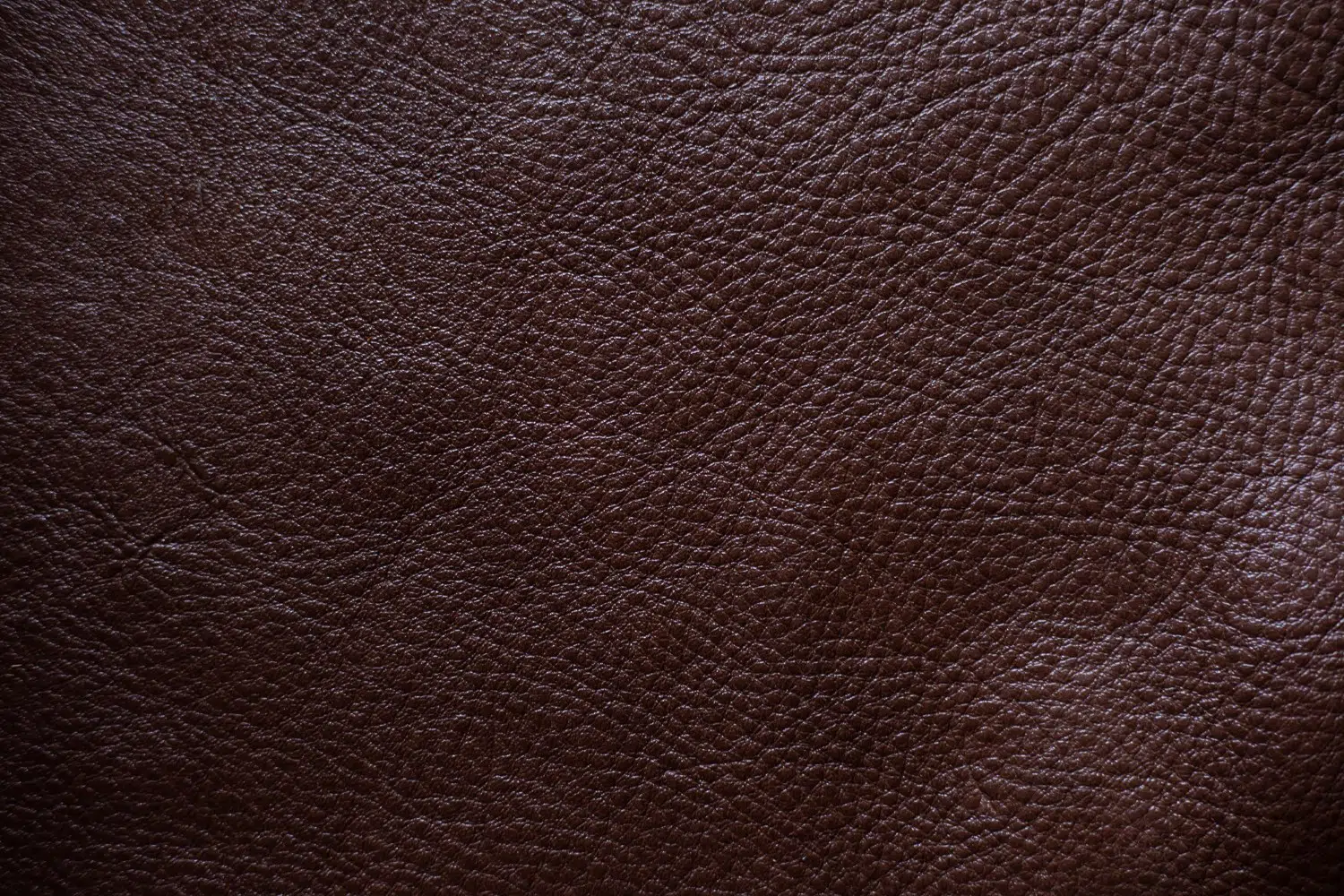

Full Grain leather is the most durable and long-wearing leather, in part, because it has already been exposed to the elements. It is still breathable and absorbs moisture and oils from handling. Again, this is a plus because it acquires a beautiful patina over time.

Don’t be disturbed if the finished product doesn’t have a uniform color or dye. This is an indication that you have a full grain product.

Top Grain Leather

Top Grain leather may also be called bookbinder or corrected grain leather. It comes from the same part of the hide as Full Grain but the very top-most layer (the grain) has been sanded or buffed. This will erase or minimize any scarring or other imperfections in the Full Grain leather.

The advantage of Top Grain leather is its smooth and uniform surface, along with its durability. Your garment, unlike a Full Grain garment, will look best on the first day you own it.

It doesn’t develop the same sort of aesthetically pleasing patina – it will just look nicked or scratched as it wears, although it is just as durable.

Top Grain leather is generally more processed than Full Grain. The curing processes seal the pores as it corrects imperfections.

You end up with a uniform depth of color and the leather will be resistant to stains and spills. It won’t absorb oils and moisture (spilled water will just bead and roll off), but also won’t be as breathable.

Top Grain leather may be embossed with an imitation print using a steel plate, high heat and pressure. It can be finished in a much wider range of colors and patterns than Full Grain leathers.

It can be slightly thinner than Full Grain so it may be preferable for items with many pattern pieces. You’ll often find Top Grain leather used for designer handbags, high-end shoes and jackets, accessories, and upholstery.

Nubuck

Nubuck is Top Grain leather that has been sanded and buffed to a matte finish. It has a fuzzy feel but isn’t has “hairy” as suede (discussed below) with a very short nap.

Nubuck is still durable and strong, without Top Grain’s ability to shed moisture. It’s used for shoes and boots, high-end work gloves, and upholstery.

Here is where there comes a major split (pun intended) in the quality of leathers. Full and Top Grain leathers are durable and come from the upper portion of the hide. All other leathers are of lesser strength, durability, and quality in varying degrees.

Split Grain Leather

Split Grain leather, sometimes called Bicast, is comprised completely of Corium. It has a lesser degree of collagen and is not nearly as durable.

It can be processed, pressurized, and dyed to look more like Top Grain, but just doesn’t have the internal structure of the top cuts of the hide.

It will have a uniform color without any real depth, and while resistant to stains and spills because of a top polymer coating, it isn’t breathable or durable.

There are times when several layers of split leather are bonded together with thin polyurethane or vinyl layers to give it strength. This type of material is generally used in products, like upholstery, where you won’t see the backing fabric.

It may also end up feeling more like plastic than leather because of the heavy processing.

Suede

Suede is made from Split Grain leather. Yes, it has a napped look like nubuck, but it’s not nearly as uniform or durable.

Looking at the diagram above, you can see how the corium cells are larger and more scattered. This is what gives the suede it’s signature “hairy” look and feel, rather than just a buffing.

It also makes it much more likely to rip or wear out. Because suede is left in an uncoated state, and not being made from the full grain layer, it absorbs water easily.

Suede is still often used in clothing, handbags, and gloves. In fact, the term suede comes from the French term gants des suede meaning Swedish gloves.

Because it is made from the bottom portion of the hide it can be split into very thin layers for a material that is drapey, pliable, and flexible.

Genuine Leather or Bonded Leather

When you see an item labeled as “genuine leather” – beware. The product can be made with as little as 10% leather, although most is in the 20-80% leather range.

This is leather scraps and dust, made into a slurry, that is then mixed with vinyl, glue, and/or plastic and bonded together.

It’s then spread on cloth or paper backing with a polyurethane adhesive to make a sheet of material. It may also have a polyurethane or latex coating. The sheet is then spray painted and/or embossed with a print to make it look like other grades of leather.

These products are not breathable, feel like plastic, smell artificial and can de-laminate and fall apart in a fairly short period of time. It doesn’t patina like other leathers.

Yet you will find Genuine Leather used for almost every type of product, from furniture to handbags and accessories, to clothing. Just know that you are probably not getting a quality product that will last for years to come.

Leather vs. Faux Leather

There are several ways to determine if an item you are looking at is real leather.

While generally not recommended for in-store trial, you can wave a lighter against leather and it won’t burn – leather is resistant to fire, although it will char and give off a distinct smell of burnt hair.

If it is fake leather (either vegan options or “genuine leather” it will quickly burn and shrivel up.

Without pulling out a match or lighter, first look at labels. Feel the texture; real leather may have an inconsistent surface pattern, minor imperfections, or uneven or varying texture. Other clues are that it should have a “warm” feel rather than cold and lifeless. After all, it was once living.

You can also try the ‘pullup’ effect. If you bend or fold real leather it will have a slight color variation. Painted or polyurethane layers are non-porous and don’t effectively absorb leather conditioners so they won’t change in color.

Similarly, you can press your finger firmly against the leather. It will wrinkle under pressure but rebound to the original shape quickly. Fake leather will retain the shape of your finger for a while and also smell like plastic.

How Leather is Dyed and Tanned

Untanned or uncured hides will be hard or rot, therefore, some type of tanning or processing is necessary. Historically, hides were brain tanned (for an explanation see our article about Moccasins).

Curing and tanning can be up to a 25-step process and is far too technical for what you need to know when shopping. There are a few terms, however, that you need to know to understand the properties of the products you’re buying.

Aniline Dying

Aniline dying uses synthetic organic compounds, usually carbon based and originally from coal-tar, to create a soluble dye that saturates the leather. They produce very brilliant, intense, and clear colors.

A very thin coat of clear or colored acrylic is applied as a final finish to help prevent instant wear of the leather.

Aniline dying is most often used on high quality Full Grain leather. You can still see the grain texture and any markings in the leather but it retains its ability to patina.

Top Grain leather can also be aniline dyed but it will have a thicker finish coat on it so it’ll be a bit shinier. This is often referred to as semi-aniline dying and the end product is actually stronger than aniline dyed leather.

Aniline dying is effective and desirable, but it also takes up to 2 weeks to dye the leather. This is why you will commonly only see it used on Top or Full Grain leathers on very expensive items.

Other types of aniline dyed leathers

Patent leather can be aniline dyed, but with a high-gloss finish applied – generally many coatings of linseed oil that are then buffed to a high-gloss finish.

It was first developed in the late 1700’s in Brussels, Belgium and later patented by Seth Boyden of Newark, NJ in 1818. Patent leather is water resistant.

Today, the linseed oil finish is usually replaced by a synthetic resin or plastic finish that has been adapted from Japanese lacquering methods.

Patent leather may look plastic, but it can actually be very fine leather. Of course, it could also be plastic. This is where knowledge of leather grading comes in handy.

Quillon leather is a smooth leather that is finished with a “haircell” or very finely textured print that gives the surface a stylish look. It was developed by Doc Marten shoes.

It has a fine gloss to it and because it is a stiff leather it takes several weeks of dedicated, daily wear to break them in. It is, however, distinctive, vintage, and durable.

Doc Marten has started making faux or vegan leather shoes that mimic Quillon leather so be aware of what you are buying.

Vegetable Tanning

Today, the most natural type of tanning is vegetable tanning. This uses the tannins, or naturally occurring acids from vegetation (barks, leaves, wood, etc.) to help stabilize the hide and strengthen the bonds within it to make it stronger.

There are a number of different trees, among them hard woods such as chestnut and oak, that are used to create the tannins used in tanning.

While the strongest leathers are vegetable tanned, they are also a bit less pliable. Items such as upholstery, saddles or holsters are often made from vegetable tanned leathers.

Conversely, shoes uppers almost never are because they would be too stiff. You will find shoe soles made from vegetable tanned leather.

Vegetable tanning is a much longer and slower process than other types of tanning; therefore, it isn’t practiced in most places. Italy is the exception – they have a consortium that continues to practice the fine art of vegetable tanning.

Vegetable tanned leathers have a rich and warm natural looking tone that will improve with age.

Because of the needed expertise, cost of materials, and processing time (up to 60 days) to properly vegetable tan leather, it is much more expensive than chemically tanned goods. It’s worth it because it will last much longer, getting better with age.

Mineral or Chrome Tanning

Most leather is chrome tanned. This is a chemical-based process that uses chromium and only takes days or even hours to finish the leather.

Chromium molecules are smaller than tannin ions so they can penetrate the collagen and remove water molecules effectively so the finished product can be thinner and softer than vegetable tanned.

In addition to being much less expensive and time consuming, it also allows much more control over what the finished product will look like. It was first introduced in 1858.

Why then, shouldn’t all tanning be chome-based? Well, for starters, it’s horrible for the environment. The heavy metals pollute the surrounding environment terribly and cause irrevocable harm to workers.

Still, because of the low cost, speed of the process, and the control it allows, 90% of today’s leathers are chrome tanned.

Types of Non-Cow Leather

While most leather you encounter is cow leather, there are a few other types that are worth mentioning.

Goat & Kidskin

Goat & Kidskin (young goats) accounts for 11% of all leathers. It’s lightweight, supple, and strong so it’s often used for gloves and ladies’ shoes.

It has a characteristic pebble grain and needs very little breaking-in time. It’s used by the US Navy and Air Force for their aviator jackets.

My all-time favorite gardening gloves are kidskin; in part because goatskin has natural lanolin in it so my hands actually felt better after working in the yard all day than they did when I started.

Pigskin

Pigskin is usually produced in China and accounts for 10% of all leathers. It’s very breathable and light weight, making it perfect for clothing.

Bison

Bison has become more popular with the increase in availability.

It has a distinctive pebbled grain and is very strong, more durable, and thicker than cow hide.

Lambskin

Lambskin is the softest, smoothest, and most lightweight of the more common leathers. It’s thinner than cowhide, has a flattering drape quality, and is used for jackets, shoes, and high-end furnishings.

Sheepskin, with the wool still attached, (sherling), is often used for coats, boots, and slippers. In total, sheep account for 12-13% of all leathers.

Horse Hide

Horse hide is used to make premium “cordovan”. The butt section of horses is used to make this very thick, smooth, and dense leather. It’s used for gloves, shoes, and small accessories.

You will often find the term “Genuine shell cordovan” used by classic shoe manufacturers as Alden, Allen Edmonds, Viberg, Rancourt, Carmina, Winter Session, and Tanner Goods.

Real cordovan is expensive ($100/square foot) and limited in quantity. It is worth it. The pores are so dense that it’s naturally water and stretch resistant and when properly looked after, a pair of shoes can last several decades.

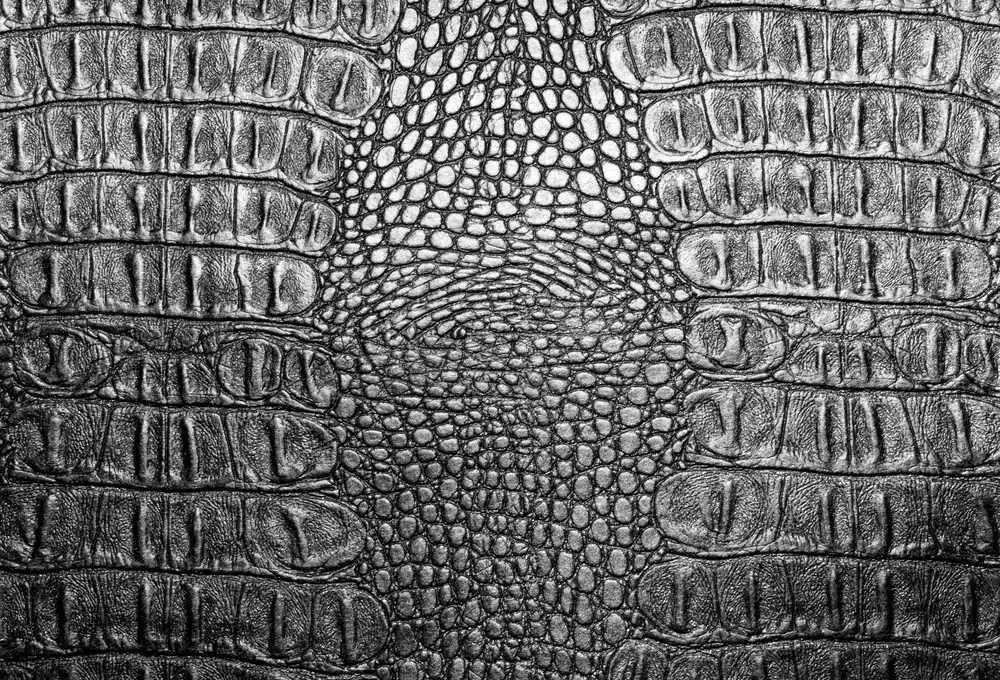

Reptile and Exotic Skins

Reptile and exotic skins account for approximately 10% of all leathers.

These may include alligator and crocodile, lizard, and ostrich skins. Reptile skins last longer and need less care than animal leathers.

That’s What You Need to Know About Leather

As you can see, there is a lot to know about leathers if you want to find the best value for your purpose.

You can think of it in terms of wood products. Aniline Top or Full Grain leather is like something made out of a thick cut of a hard-wood tree that has been minimally finished with an oil or wax finish.

You can see the life of the tree in the rings, yet it’s strong and beautiful in its imperfections. Genuine Leather is like particle board, or even corrugated cardboard. While it’s less expensive, it won’t last in the long run, although it has its place in our lives.

While quality leather is expensive, if you think of it in terms of longevity and enjoyment, it’s a good value. Fine leathers will last decades or even a lifetime with proper care. Many only improve with time and use.

But you have to know what you are looking at to find it so knowing the basic terminology and grading systems is imperative.

Questions? Comments? Leave them below!

Ask Me Anything